Doe Steam Training With the Morris Museum of Art March 5

| Robert Morris | |

|---|---|

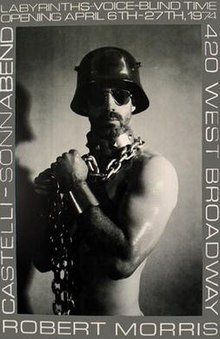

The "infamous" 1974 self-constructed torso art poster of Robert Morris by Rosalind Krauss | |

| Built-in | (1931-02-09)February 9, 1931 Kansas Metropolis, Missouri, U.Due south. |

| Died | November 28, 2018(2018-xi-28) (aged 87) Kingston, New York, U.Due south. |

| Education | University of Kansas, Kansas City Art Institute, Reed Higher, Hunter College |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Movement | Minimalism |

| Spouse(s) | Simone Forti, Priscilla Johnson, Lucile Michels |

Robert Morris (February 9, 1931 – Nov 28, 2018) was an American sculptor, conceptual creative person and writer. He was regarded every bit having been i of the most prominent theorists of Minimalism[1] along with Donald Judd, but also made important contributions to the development of performance art, land art, the Process Art motion, and installation art.[ii] Morris lived and worked in New York. In 2013 as role of the Oct Files, MIT Press published a volume on Morris, examining his work and influence, edited past Julia Bryan-Wilson.[3]

Early life and education [edit]

Born in Kansas City, Missouri to Robert O. Morris and Lora "Pearl" Schrock Morris. Between 1948 and 1950, Morris studied engineering at the University of Kansas.[four] He then studied art at both the University of Kansas and at Kansas Metropolis Fine art Institute every bit well as philosophy at Reed College [1]. He interrupted his studies in 1951-52 to serve with the Us Army Corps of Engineers[v] in Arizona and Korea.[4] He married dancer Simone Forti in 1955[ii] and afterward divorced in 1962. After moving to New York City in 1959 to study sculpture, he received a master'south degree in art history in 1963 from Hunter College.[4]

Work [edit]

Initially a painter, Morris' work of the 1950s was influenced by Abstract Expressionism and especially Jackson Pollock. While living in California, Morris besides came into contact with the work of La Monte Young, John Cage, and Warner Jepson with whom he and starting time wife Simone Forti collaborated. The idea that art making was a tape of a performance by the creative person (fatigued from Hans Namuth's photos of Pollock at work) in the studio led to an interest in dance and choreography. During the 1950s, Morris' furthered his involvement in dance while living in San Francisco with his wife, the dancer and choreographer Simone Forti.[6] Morris moved to New York City in 1960. In 1962 where he staged the performance Cavalcade at the Living Theater in New York[7] based on the exploration of bodies in space in which an upright square cavalcade after a few minutes on stage falls over.

Bronze Gate (2005) is a cor-ten steel piece of work past Robert Morris. It is gear up in the garden of the dialysis pavilion in the hospital of Pistoia, Italy.

In New York Urban center, Morris began to explore the work of Marcel Duchamp, making conceptual pieces such equally Box with the Audio of its Ain Making (1961) and Fountain (1963). In 1963 he had an exhibition of Minimal sculptures at the Green Gallery in New York that was written nigh past Donald Judd. The following year, too at Greenish Gallery, Morris exhibited a suite of big-scale polyhedron forms constructed from 2 x 4s and gray-painted plywood.[8] In 1964 Morris devised and performed two historic performance artworks 21.iii in which he lip syncs to a reading of an essay by Erwin Panofsky and Site with Carolee Schneemann. Morris enrolled at Hunter Higher in New York (his masters thesis was on the work of Brâncuși) and in 1966 published a series of influential essays "Notes on Sculpture" in Artforum. He exhibited 2 Fifty Beams in the seminal 1966 exhibit, "Primary Structures" at the Jewish Museum in New York.

In 1967 Morris created Steam, an early piece of Land Fine art. By the late 1960s Morris was being featured in museum shows in America but his piece of work and writings drew criticism from Clement Greenberg. His piece of work became larger scale taking up the majority of the gallery space with series of modular units or piles of earth and felt. Untitled (Pink Felt) (1970), for example, is composed of dozens of sliced pink industrial felt pieces that have been dropped on the floor.[8] In 1971 Morris designed an exhibition for the Tate Gallery that took up the whole cardinal sculpture gallery with ramps and cubes. He published a photo of himself dressed in S&M gear in an advertizing in Artforum, similar to one by Lynda Benglis, with whom Morris had collaborated on several videos.[9]

He created the Robert Morris Observatory in the Netherlands, a "modern Stonehenge", which identifies the solstices and the equinoxes. Information technology is at coordinates 52°32'58"N 5°33'57"Due east.

During the afterward 1970s, Morris switched to figurative work, a move that surprised many of his supporters. Themes of the work were often fright of nuclear war.[10]

In 2002, Morris designed a set of seventeen pale bluish and beige-coloured stained-glass windows for the medieval Maguelone Cathedral, near Montpelier in France. The windows, which draw the ripples of a pebble dropped in water, were produced past Ateliers Duchemin glassmakers and placed in restored romanesque window lights effectually the cathedral building.[xi]

At the fourth dimension of his decease in late Nov 2018 an showroom of Morris' recent work "Banners and Curses" was on brandish at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City. The exhibition ran through January 25, 2019. Morris attended the opening night reception for the bear witness at the gallery.[12]

Death [edit]

Morris died on November 28, 2018, in Kingston, New York, from pneumonia at the historic period of 87.[13] He had married Lucile Michels in 1984. He is survived by his wife Lucile and a daughter Laura Morris.[14]

Artist books [edit]

- Hurting Horses, 64 pages, 23,5 x 16,5 cm. Express edition of 1500 copies. Produced and published in 2005 by mfc-michèle didier.

Writing [edit]

- Continuous Project Contradistinct Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, October Books, MIT Press [ii]

- 'Notes on Sculpture [iii]

Disquisitional reception [edit]

In 1974, Robert Morris advertised his brandish at the Castelli Gallery with a poster showing him blank-chested in sadomasochistic garb. Critic Amelia Jones argued that the torso poster was a statement about hyper-masculinity and the stereotypical idea that masculinity equated to homophobia.[15] Through the poster, Morris equated the power of art with that of a physical force, specifically violence.[16]

Robert Morris's fine art is fundamentally theatrical. (…) his theater is ane of negation: negation of the avant-gardist concept of originality, negation of logic and reason, negation of the want to assign uniform cultural meanings to various phenomena; negation of a worldview that distrusts the unfamiliar and the unconventional. (Maurice Berger, Labyrinths: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s, p. 3.)

In Morris' volume, Continuous Project Contradistinct Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, the artist includes a collaborative projection with the fine art critic G. Roger Denson in which he lampoons the criticism of his piece of work published over the course of his career up to the early 1990s. The chapter, entitled "Robert Morris Replies to Roger Denson (Or Is That a Mouse in My Paragon?)", lists thirteen questions submitted by Denson, with each question representing the criticism of Morris' work written past a different unnamed critic responding to a specific exhibition, installation, or art work. Instead of answering the questions, Morris has written an elaborate, comically absurd, satirical narrative that in many ways epitomizes the "only possible response" to criticism that had become fashionable in the and then-called "demise of criticism" that some writers of the 1980s and 1990s heralded following the "deconstruction of logocentrism" postulated past the post-structuralist theorist Jacques Derrida. As i commentator, Brian Winkenweder, wrote:

"In his reply [to Denson'south questions], Morris compartmentalized diverse aspects of his oeuvre into nine, cleverly-named alter-egos such every bit Body Bob, Major Minimax, Lil Dahlink Felt, Mirror Stagette, Clay Macher and Blind. He too appropriated the brick-hurling Ignatz Mouse from George Herriman's comic strip Krazy Kat as rhetorical flourish to enhance his written answers to Denson's questions."

Winkenweder so cites the mockery to which Morris' critics are subjected in his absurdist satire, as bricks are hurled at each of Denson's questions.

"Hey, what'south going on, Ignatz? Everybody is rolling on the floor and laughing. I've never seen such a hysterical gang of assassins. What, you read that ticket about our 'new tone of ironic self-reference?' And what? Body Bob threw the I-Box at the Major who then bent Stagette out of shape with the Corner Piece and Bullheaded smeared loving cup grease on Dirt Macher'south … wait a minute, Ignatz. You started this bedlam by throwing bricks at everyone, I bet....Get Torso Bob out of that Kraut helmet immediately…No, I did not give it to Lil Dahlink Felt with the Card File. How could you retrieve such a thing, Ignatz? Y'all are and then surly today. Why don't I punch my own ticket?" (Morris, 1993, 307).[17]

Exhibitions [edit]

Morris' first exhibition of paintings was held in 1958 at the Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco.[4] Numerous museums have hosted solo exhibitions of his work, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (1970), the Art Institute of Chicago (1980), the Museum of Contemporary Fine art, Chicago and the Newport Harbor Art Museum (1986),[4] and the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (1990). In 1994, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, organized a major retrospective of the creative person's work, which traveled to the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg and the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris.[6]

Notable Works [edit]

- Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961), Seattle Art Museum

- Steam Work for Bellingham-II (1974), Western Washington University Public Sculpture Collection, Bellingham, Washington

- Untitled (L-Beams) (1965), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

- Labyrinth, 1982 Gori Drove, Italia

Art marketplace [edit]

As a conceptual artist, Morris at times contractually removed from circulation. When a collector, the builder Philip Johnson, did not pay Morris for a piece of work he had ostensibly purchased, the artist drew up a certificate of deauthorization that officially withdrew all aesthetic content from his piece, making information technology nonexistent every bit fine art.[xviii]

See also [edit]

- Robert Morris Earthwork

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Robert Morris," Encyclopedia of visual artists. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ a b Lexicon of Modernistic and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 481

- ^ "Robert Morris". MIT Press . Retrieved July thirteen, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Josine Ianco-Starrels (Apr 27, 1986), Robert Morris Works Focus On Environment Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Robert Morris Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- ^ a b Robert Morris Archived Jan 16, 2013, at the Wayback Automobile Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- ^ Cindy Hinant, A Subversive Practitioner (2014). Meyer-Stoll, Christiane (ed.). Gary Kuehn: Betwixt Sex and Geometry. Cologne: Snoeck Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 32–33, 36. ISBN3864421098.

Cavalcade was staged in February 1962 at the Living Theatre, New York, and features an element from Morris's earlier piece of work Two Columns, 1961, which consisted of two 8-foot-high rectangular plywood boxes painted gray. In the performance of Column, one of these boxes was placed vertically on an empty phase for three-and-a-half minutes, and so a string was pulled, causing it to fall on its side, where information technology lay for some other three-and-a-half minutes.

- ^ a b Robert Morris, Untitled (Corner Slice), 1964 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- ^ Taylor, Brandon (2005). Contemporary Art: Art Since 1970. London: Prentice Hall. p. 30. ISBN0-xiii-118174-2.

- ^ Lexicon of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford Academy Press. 2009. p. 482

- ^ "Robert Morris - Maguelone Cathedral, France". Ateliers Duchemin. Archived from the original on September 6, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ "Robert Morris, the conceptual sculptor and leading Minimalist, has died, aged 87". www.theartnewspaper.com . Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Morris, Sculptor and a Founder of the Minimalist School, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Nov 29, 2018.

- ^ "Obituary for Robert Morris". Copeland Funeral Home. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Jones, Amelia (1998). Body Fine art/Performing the Subject. Academy of Minnesota Press. pp. 114–115.

- ^ Chave, Anne C. (1991). "Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power". In Holliday T. Mean solar day (ed.). Power: Its Myths and Mores in American Fine art, 1961-1991 . pp. 134.

- ^ Brian Winkenweder, "The Homometrics of eInterviews." In Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture (9.1, 2009): http://reconstruction.eserver.org/091/winkenweder.shtml

- ^ Kingdom of the netherlands Cotter (November 1, 2012), Works That Play With Time New York Times.

References [edit]

- Berger, Maurice. Labyrinths: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s, New York: Harper & Row, 1989

- Busch, Julia K., A Decade of Sculpture: the New Media in the 1960s (The Art Alliance Press: Philadelphia; Associated Academy Presses: London, 1974) ISBN 0-87982-007-1

Further reading [edit]

- Nancy Marmer, "Death in Black and White: Robert Morris," Art in America, March 1983, pp. 129–133.

External links [edit]

- Robert Morris at the Museum of Modern Art

- Guggenheim Robert Morris bio

- Robert Morris, Publicportfolio at columbia.edu

- Robert Morris in the Video Data Banking concern

- Country Reclamation und Erdmonumente article in German language by Thomas Dreher

- Observatory almost Lelystad/Oost Flevoland in Netherlands, illustrations

- Allan Kaprow versus Robert Morris. Ansätze zu einer Kunstgeschichte als Mediengeschichte commodity in German by Thomas Dreher on the competing theories on art by Allan Kaprow and Robert Morris

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Morris_(artist)

0 Response to "Doe Steam Training With the Morris Museum of Art March 5"

Post a Comment